Save the Envelope! Research with Postage Stamps and Covers for Non-Philatelists

Are you a researcher or archivist faced with philatelic records and unsure of where to begin? Here is a crash course in the basics of philatelic records.

This is an adapted version of a lightning talk presented by the Greene Foundation’s library manager, Natalie Mitchell, at the Government Information Day(s) virtual conference in December 2024. This conference brings together government information colleagues from across Canada and beyond. It is an opportunity for librarians, archivists, journalists and scholars who are involved with government information in some way to share what they are working on and are concerned about.

As you might have guessed based on the title of this blog post, philately refers to the collection and study of postage stamps. Postage stamps and postal markings are evidence of a government at work, and they inform researchers on how the mail got from sender to addressee. Often these routes of travel for letters and the rates of postage are evidentiary of broader historical context, and can be just as interesting as the letters themselves. Though less common now, many archives once chose to discard envelopes from manuscript collections or collections of personal papers. This choice was often made to reduce bulk in collections, or because these envelopes were not thought to have any research value. Saving these envelopes and conducting research with them preserves valuable context and can enhance a record’s meaning within a collection.

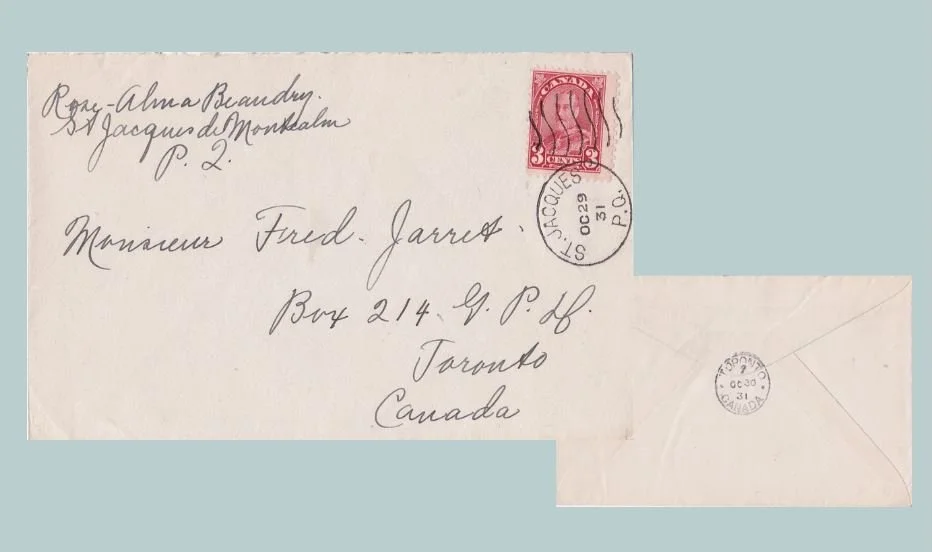

Let’s start with some basic terminology so you’ll be better equipped to identify the details of an envelope. This will likely be a review for many readers, as you have probably sent a letter at some point in your lives. For this example, we’re using a cover, a philatelic word for “envelope,” from the Greene Foundation's own collection. This cover was sent to Fred Jarrett: the only individual to be inducted into the Order of Canada for his philatelic work.

Looking at the components of this cover reveal pieces of its postal history, which is a component of philately, and is the study of the operation of the postal system. It includes the study of postmarks, post offices and postal authorities, postal rates and regulations, and the movement of the mail.

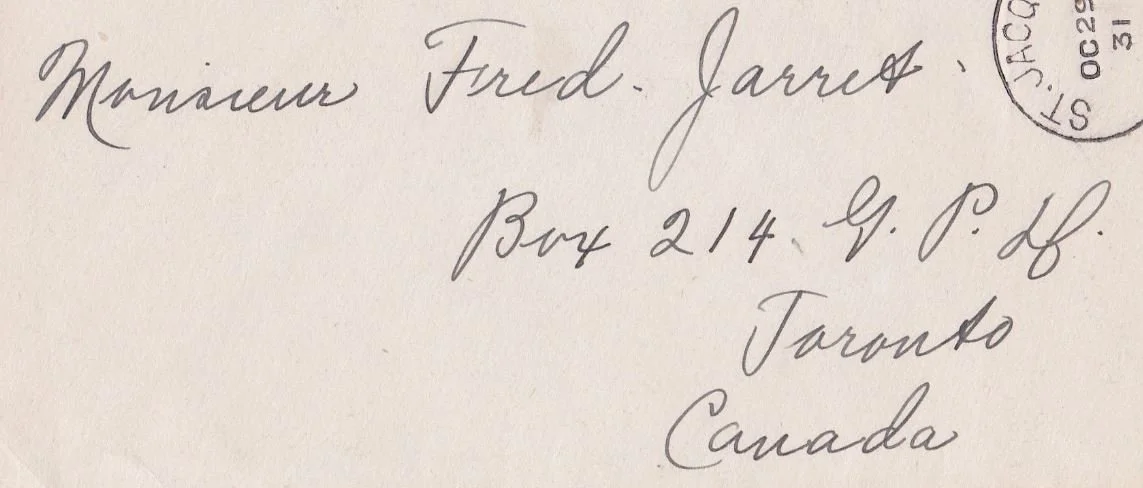

The addressee is in the centre of the cover. This shows the destined recipient and their location. Sometimes this section can also reveal what the relationship is between the sender and addressee with familial words such as sister, father, or honorifics that designate a formal relationship.

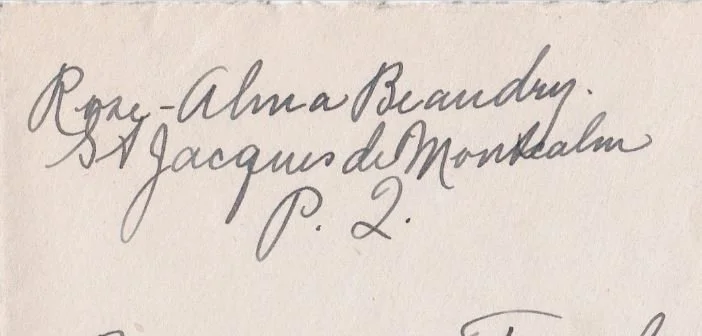

In the upper left corner is the return address, which typically belongs to the sender of the letter, but not always. There have been cases in which a sender did not want to pay postage, so they would write the addressee’s name and address in the return address spot rather than their own, post the letter without a stamp, and then it would be returned to the intended recipient rather than the sender! As you can imagine, postal authorities have cracked down on this.

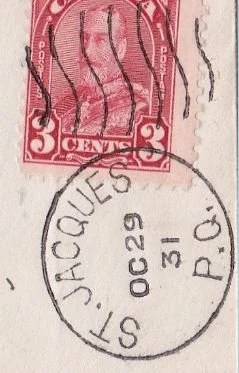

The stamp shows how much was spent to send the letter, or the rate of postage. In the case of this letter, it was paid correctly. The standard domestic letter rate in 1931 was 3 cents. Not only are stamps governmental instruments of postal operations, but they’re also interesting emblems of culture. They can tell us what a government wants to be associated with, what they value, or who they honour in their official national memory. Sometimes stamps are chosen by senders for particular reasons, or are placed in a way to send a particular message. This can be as simple as a spooky stamp being chosen for a Halloween card, or can be more nuanced, with a stamp pasted upside down on a letter having symbolized deep affection or love for the addressee going back to the Victorian period.

The postal markings, cancellations, or obliterations applied by postal officials also tell a story. Generally, they show how the letter got from point A to point B. In this letter’s case, it was posted in Saint-Jacques, Quebec on October 29, 1931 and arrived in Toronto the next day, as you can see by the marking on the reverse. Cancellations such as this were specific to the post office which processed the letter, so you are able to identify exactly where the letter was sent. Specialist postal historians can sometimes even identify exactly which postal worker would have cancelled the letter during certain periods because specific obliterators were assigned to individual postal employees.

If you would like to see some postal history in action, please check out some of our other blog posts on this site! The L.M. Montgomery post or the Bangkok to Angers cover story are great places to start.

If you would like to learn more about philately, feel free to check out our Stamp Collecting 101: Books for Beginners blog post, or send us an email at library@greenefoundation.ca.

— Natalie Mitchell

Library Manager, Greene Foundation